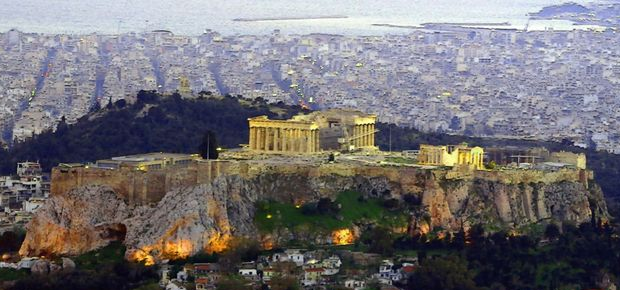

1.1 The City-State in the classical world

The Greek word polis, from which words such as political, in the classical sense meant "a state that governs itself". The greatest polis, Athens, had a surface area of about 1700 sq km. Call it the City-State meant give it an improper definition for two reasons: it neglects the rural population, which formed the majority of citizenship, and suggests that the city govern the country, what is wrong. Athens, to the extent and quality of its urbanization, was at one end of the size scale of the Greek cities, together with a relatively small number of other states. At the other extreme there were other states that were not city, although they possessed all their civic centers. When Sparta, for example, in 385 defeated Mantinea, who was then ruling the polis in Arcadia, demanded that the city was razed to the ground and that people come back to the villages from which at one time was coming. From the account of Xenophon is clear that the disappointment caused by this imposition, it was only political and psychological. The inhabitants of the city of Mantinea, were owners of large tracts of land, and preferred to live in the united center, away from their possessions, in a style that can be traced already in the Homeric poems and that he had to do much with the city life. The figures on the size of the Greek cities are all speculative because we do not have exact directions.

When the Athenian population reached its maximum, at the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431, the total, including men, women and children, free and slave, a di 250 mila o di 275 thousand inhabitants. No other Greek polis never came to this figure until the Roman period, when conditions changed completely. Corinth could count 90 thousand inhabitants, You, Argo, Corcyra and Agrigento dai 40 to 60 thousand each, and other cities followed at a distance, with many 5 thousand inhabitants and less.

Thucydides says that piracy on land and sea was honorable occupation among the Greeks as among the barbarians. The word polis did not distinguish the structure of government; did not imply anything, that the word was no longer, about democracy, oligarchy or tyranny. In the broadest sense of the term, he identified the polis by any independent Greek community, or that he had temporarily lost its independence. The polis was not a geographical place, although it occupied a defined territory: population was active by mutual agreement, and therefore had to be able to come together and deal with its problems in common. This was a necessary condition, although not the only, of self-. Self-sufficiency was another condition that could allow true independence. However, the polis was not to be so small as to lack of manpower needed to keep the various activities of a civilized existence, including the needs of the defense. If the population size were adequate, nevertheless there was the problem of sharing the rules of conduct and organization of social life. The answer the Athenian and Spartan response to these problems were radically different. In Athens, for example, not all accepted the sharing of these rules of coexistence and hence the long and complicated political debate that took place there. Queso debate took place in a small closed circle within the total population, because the polis was an exclusive community. In the middle of the fifth century, the Athenians adopted a law that restricted citizenship to the children of parents who are both legitimate offspring of town. There was a time in which in which the Greek aristocrats combined marriages for their children, often outside of the community, sometimes even with the barbarians, although only with the leaders. Under the rule of Pericles, Athens outlawed marriages these bastards and their children.

The word "citizen" does not make, at least in our day, all the implied value of belonging to the community of the polis. And for those who were not born in the community, it was almost impossible to enter fully. An alien could become a citizen of Athens only by a formal act of the Assembly sovereign, and historical records indicate that very special considerations were necessary before the meeting could be persuaded. For example, was not enough to be born in Athens, serve in his army and behave properly and fairly, if he had not the children of citizens. Throw open the doors to foreigners was no sign of any defect, and not just a coincidence that the end of the fourth century, some city-states were forced to sell citizenship to increase revenue, and this happened in the period in which the classical polis was a body now declining.

Especially in the city-state more urbanized and more cosmopolitan, the real community was constituted by a minority. The majority included in non-citizens, including permanent residents in Athens and some other cities were called "metics", slaves, who formed a class even more numerous, and, in principle, all women. Whatever their rights, and what was left entirely to the power of the state, they were under various restrictions, compared to nationals, and at the same time were completely subject to the authority of the state in which they resided. The polis was the source of all rights and obligations and all its authority pervaded every sphere of human behavior. There were things that did not, however, a state greek, as for example, provide higher education or control interest rates, but his right was still out of the question, although he chose not to do so. The polis not escaped. But if the polis had unlimited authority so, the sense in which the Greeks considered themselves free? The answer is contained in an epigram: "The law is king". The freedom was not identified with anarchy, but with a life ordered within a community that was established and governed by a code shared by all. The fact that the community was the only source of law, was a guarantee of freedom. On this point all could agree, but translate the principle into practice was another matter; Hence the classical Greek collided with a difficulty that has been in political theory without finding a safe solution. As the community was free to change its laws established? If the laws could be changed at will, ie from any faction or group at any time occupy a position of dominance in the state, this would not lead to anarchy, to undermine its stability and security that were implicit in the doctrine that proclaimed that "the law is king"? The answer to these questions depended on the respective protagonists. The sixth century saw the emergence of the common people in many communities as a political force, and against its demand for full participation in the government, was promptly opposed the defense of the sanctity of the law, a code that, While recognizing the right of every citizen to a fair trial, maybe to a small participation in the government, or even to draw, and other important areas of social, however, limited to the nobles and the wealthy senior civil and military offices, and then the active policy. Eunomia, it was well-ordered and governed by the law, at one time had been a revolutionary slogan; now indicated the status quo, preservation. The people responded by claiming a new condition, l’ isonomia, equality of political rights, and since the people had the numerical majority, the isonomy led to demokratia.

In the polis, the strong sense of community struck against the great inequality among the members that there was. The misery was widespread, the material standard of living was low, with a deep divide between rich and poor. The citizen felt he had the rights to the community and not only obligations. If the system of government did not satisfy him, he was ready to do anything, to get rid of it, the poteva. Consequently, in classical Greece, the dividing line between politics and sedition (stasis) was thin, and very often the stasis turned into civil war. Aristotle says in Politics: "Generally, prating, men resort to stasis desire for equality ". In the Greek polis, Athens and in particular up to a certain point Sparta, the most serious divisions were caused not so much by politics as by the question of who should rule, if "few" or "many". And the issue was also complicated by external business, by war and imperial ambitions. In the war against the Persians of King Darius, and then his successor Xerxes, by Greek Sparta only possessed a powerful army but, for a strategic concept wrong, made a dilatory defense, although at the time of trial, at Thermopylae and later at Plataea, showed great courage. It was then Athens to deal the decisive blows at Marathon in 490 and off the coast of Salamis in 480. This last battle, fought on the sea, represented an important turning point: convinced by Themistocles, the Athenians increased rapidly the number of ships in the fleet, abandoned the city to the arrival of the Persians, and left it to be destroyed; then, with their allies, crushed the invading Persians in the great naval battle of Salamis. From that moment on,, the power of Athens, and then the whole history of classical Greece, depended on control of the sea. In the quarter century that followed, Athenian dominance was the most important factor in Greek political life, Pericles and emerged as the dominant figure in Athenian life. Ma presto well, as Thucydides wrote, "The increase of the power of Athens, and the alarm that it inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable ". Peloponnesian War, which lasted, with some interruptions, from 431 to the 404, ended with the total defeat of Athens and the dissolution of his empire. Pericles died in the second year of the war. In the fourth century the power vacuum in Greece became permanent, despite efforts to shift from Sparta, Thebes and Athens to establish some kind of hegemony. The final answer, however, was not a state but from the greek Macedonia, Philip II and his son Alexander.