1.15 The Painting

The history of Greek painting must be written on the basis of the testimonies of the ceramic, as well as on the basis of literary references. Since 1000 about, con Atene, began to appear top quality ceramic tiles, in large part, decorated only with geometric designs. When later were introduced human figures, also were very stylized and grouped in a way that constitutes rather an extension of geometric forms. With subsequent developments, technique, the shape and decoration made great advances. The painted pottery of practical use had spread universal among the Greeks, wherever they migrated. Part of it was also exported to the neighboring barbarians at. The Etruscans and other Italic peoples they imported in large quantities and they also fabricated imitations, but civilized peoples Eastern never showed the slightest interest in it. Although the Greek cities produccessero your own pottery cheap, eventually most of them decided to leave in very few hands produce more refined: first in Corinth, and after the mid-sixth century, almost exclusively in Athens.

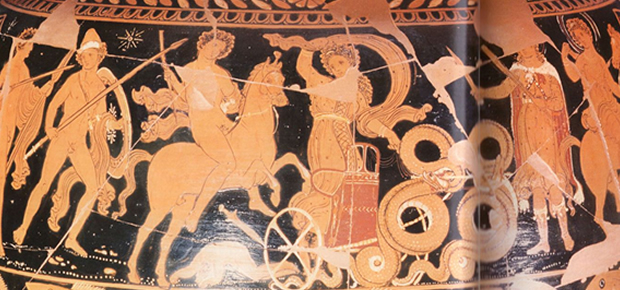

The painting of Corinthian pottery was purely decorative. The pottery was designed for everyday use, and therefore it was decorated in order to make it nice, not to make the works of art. The Athenians excelled in covering scenes of mythical or heroic curved surfaces, often complex compositions. In the first phase, which reached its climax during the tyranny of Pisistratus, they used a plain black background clay that, after cooking, had a predominantly orange color but tending, and ogni vaso, or towards yellow or red towards the. Towards the end of the sixth century, The technique was invented to reverse the process, covering of black bottom and leaving the actual painting in the color of terracotta. This new style is called, by convention, a figure rosse, while the former is called black-figure. Over a twenty year, the red-figured vases prevailed, and other, a figure nere, practically disappeared.

Much pottery was used for religious purposes, to be buried in the graves or to contain oil for libations, and the designs were appropriate: scene mourn, or mythological or similar. But for the most part the objects were made for personal use common, and then the themes were unlimited: those mythological and military to domestic, sometimes obscene or grotesque. In this respect, the painters of the vessels had a freedom that was denied to the sculptors and used it with panache and wonderful fantasy. The paintings lacked depth because the curved surface of the ceramic pots would have been very difficult the use of perspective. Even if some colors were added, and in the fifth century were produced beautiful vases with a background of white paste which produced an effect quite different from those reds and blacks, the field remained restricted and could cause them to not deny a certain monotony. This impression was accentuated due to the use of constant linear design in all the figures, that excluded the chiaroscuro with all its possibilities. Around, however, There was some attempt to overcome these limitations, under the influence of wall paintings and panels. The figurative painting on vases disappeared towards the end of the fourth century.

The mural was widespread, probably beginning with the rebirth of monumental. Was limited to public buildings including the royal palaces of the Hellenistic, and its development was much slower architecture and sculpture. Little by little the painters learned to model the figures with lights and shadows, and to create an illusion of three dimensions. The most celebrated painter of ancient Greece was Apelles, lived in the fifth century, a century later by Phidias. He was court painter to Alexander. The greatest sculptor, Fidia, was closely associated with Pericles, while the greatest painter, Apelle, with the conqueror and monarch with which began the Hellenistic.